DrSamGirgis.com has the pleasure of hosting the following post by contributing blogger, Dr. Richard Andraws MD, who is a Board Certified Cardiologist

Knowing a great deal is not the same as being smart; intelligence is not information alone but also judgment, the manner in which information is collected and used.

–Carl Sagan

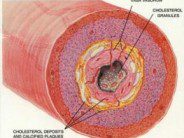

The implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) has revolutionized the care of patients at risk for sudden death due to dangerous arrhythmias. Every year a quarter million Americans die suddenly from rapid, disorganized heart rhythms arising from the heart’s pumping chambers, or ventricles. These rhythms are due most commonly to coronary disease that weakens and scars the heart. If not treated promptly with a shock, these arrhythmias lead to progressive circulatory collapse and death within minutes. The ICD is a special pacemaker that senses these electrical abnormalities and appropriately treats them within seconds of detection. On top of best medications, ICDs have been shown to reduce the risk death by an additional third.

We’ve realized that certain factors predict higher risk for sudden death. A weakened heart that pumps poorly is probably the single most important criterion we have. In fact, if a person’s heart remains feeble despite medications and other procedures (like angioplasty or bypass surgery), they qualify for a “primary prevention” ICD to prevent a fatal arrhythmia from ever occurring. There’s no guarantee that person will ever experience an arrhythmia and may never need therapy from the ICD. Moreover, there’s always a risk of “inappropriate” therapy (when the ICD mistakes a benign rhythm for a malignant one and shocks the person). And then there are the larger existential questions: what if a patient at risk for sudden death who has an ICD also develops terminal cancer? Should we prolong life futilely in the final days? Should we compromise any remaining quality of life with the specter of unpleasant, inappropriate shocks?

So when the ICD battery gives out after five or seven years—what do we do? Automatically replace it and commit the patient to another decade of therapy?

Two intriguing papers examine this question from different perspectives. The first from Van Welsenes and colleagues looks at whether we should be replacing ICD batteries if the patient did not receive any therapy the first time around. Have we thus proven the patient doesn’t need an ICD? The authors followed 114 patients who had never received therapy for a mean of two years after replacement of their batteries. They found that the cumulative incidence of an appropriate shock in the 3 years after the replacement was 14%. That number is far from negligible and proves that while the majority of patients (74% in their cohort) may not need their ICDs for years, they’re never totally out of the woods.

The other is a Perspective piece from Kramer and colleagues in the New England Journal of Medicine. They tackle the larger question of whether ICD therapy ever causes harm. When is it time to say enough and not continue therapy by replacing the battery? They strongly encourage frank discussions between patients and their physicians regarding their current state of health and goals for end of life. In addition, they stress that physicians (primary care docs and specialists) should be talking to each other about shared patients. Specialists should not fear lost referrals if they don’t robotically “replace the can,” and perhaps the system shouldn’t incentivize specialists to do so. Finally, the authors call for trials to better elucidate in which populations continued ICD therapy makes clinical and economic sense.

Hippocrates’ fundamental philosophy can be found in his Of the Epidemics: “The physician must…have two special objects in view with regard to disease, namely, to do good or to do no harm”. Knowing what can be done without the wisdom to seek and understand what should be done for patients surely does them a grave disservice.

FURTHER READING

Van Welsenes GH, Van Rees JB, Thijssen J, et al. Primary Prevention Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator Recipients: The Need for Defibrillator Back-up After an Event-free First Battery Service-life. J CardiovascElectrophysiol.2011; 22:1346-1350.

Kramer DB, Buxton AE, Zimetbaum PJ. Persepctive: Time for a Change — A New Approach to ICD Replacement. N Engl J Med 2012; 366:291-293.

DrSamGirgis.com is a blog about medicine, nutrition, health, wellness, and breaking medical news. At DrSamGirgis.com, the goal is to provide a forum for discussion on health and wellness topics and to provide the latest medical research findings and breaking medical news commentary.

DrSamGirgis.com is a blog about medicine, nutrition, health, wellness, and breaking medical news. At DrSamGirgis.com, the goal is to provide a forum for discussion on health and wellness topics and to provide the latest medical research findings and breaking medical news commentary.

{ 0 comments… add one now }