DrSamGirgis.com has the pleasure of hosting the following post by guest blogger, Dr. Richard Andraws MD, who is a Board Certified Cardiologist

Success consists of going from failure to failure without loss of enthusiasm.

–Winston Churchill

Atrial fibrillation (A-Fib) is the most common arrhythmia (abnormal heart rhythm) seen in adults. By the age of 80, approximately 10% of Americans are diagnosed with it. Aside from age, predisposing factors include high blood pressure, thyroid and heart valve disease, and heart failure, among others. Certain genes are increasingly being recognized as contributing and likely explain early onset A-fib in otherwise healthy people. A-fib can be asymptomatic, but palpitations, fatigue, light-headedness and shortness of breath are common due to the characteristically rapid, irregular heart rate. The most feared complication is stroke. Strokes are caused by escaped clots that form in the heart’s paralyzed upper chambers.

A-Fib is treated in several ways. Most patients must take blood thinners indefinitely to prevent clot formation and strokes. Patients with few or no symptoms can be placed on medications to slow and control their heart rates. However, in patients with significant symptoms, restoring and maintaining normal rhythm with anti-arrhythmic drugs (AADs) is preferable. Yet even in the best of cases, AADs are only 60-70% effective long term.

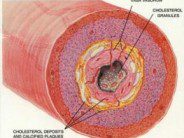

In 1994, a group of French cardiologists led by Michel Haïssaguerre described the process of A-Fib ablation. The heart was entered through veins in the thigh with tiny, flexible tubes called catheters. These catheters were used to record the electrical activity of the heart and deliver heat to targeted areas thought responsible for perpetuating A-fib. The heat destroys (or “ablates”) the abnormal areas and leaves the normal ones intact. It was theorized that restoring normal rhythm by physically transforming the heart could possibly “cure” A-fib. While there has been an explosion of technology and techniques in the last two decades, cardiologists have not been able to achieve a cure.

And so Winkle and colleagues, in a recent issue of American Heart Journal, bring us up to date on the current state of ablation. They reviewed the experience at a single center where 843 patients underwent ablation from 2003 to 2009. More than 70% of the subjects were male and had failed at least one AAD. Female patients were older, more commonly had high blood pressure and were in A-fib for a shorter time. Men more commonly had heart failure. The same ablation technique was used in all patients. Patients received AADs for 3 months after a procedure but then were followed off medication.

After a single ablation procedure, 45-70% of patients were in normal rhythm at one year. With one or two repeat procedures, 70-90% of patients were A-fib free at one year; by four years the figure had fallen somewhat to 60-80%. Age, structural heart disease, duration of A-fib prior to ablation, and female sex correlated to failure to maintain normal rhythm. Female sex may have contributed due to fewer repeat procedures among women. Ablation appeared safe, with a complication rate of 3-4% (slightly higher with repeat procedures) and with no deaths directly related to the procedure (within 30 days).

The authors cite evidence that repeat ablations appear to help the heart remodel and make elimination of A-fib more likely. They note that they might be overestimating success as close follow-up of patients for recurrence diminished over time. Likewise, complications may have been underestimated as some could have been asymptomatic. The study specified only 3 months of AAD use after ablation. It would have been interesting to see what the “cure rate” may have been with long term AADs in addition to ablation.

The take home message is that A-fib ablation is a useful, albeit imperfect option for symptomatic patients who fail AADs alone. Patients should understand that the road to benefit is not straightforward, and ablation may not completely obviate the need for medications, including blood thinners. But staying on a path paved with enthusiasm, even in the face of initial failure, is most likely to lead to better health.

REFERENCES:

Winkle RA, Mead RH, Engel G, et al. Long-term results of atrial fibrillation ablation: the importance of all initial ablation failures undergoing a repeat procedure. Am Heart J 2011; 162:193-200.

2011 ACCF/AHA/HRS Focused Updates Incorporated Into the ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation J Am Coll Cardiol 2011; 57:101-198

Haïssaguerre M, Gencel L, Fischer B, et al. Successful catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 1994; 5: 1045-1052.

DrSamGirgis.com is a blog about medicine, nutrition, health, wellness, and breaking medical news. At DrSamGirgis.com, the goal is to provide a forum for discussion on health and wellness topics and to provide the latest medical research findings and breaking medical news commentary.

DrSamGirgis.com is a blog about medicine, nutrition, health, wellness, and breaking medical news. At DrSamGirgis.com, the goal is to provide a forum for discussion on health and wellness topics and to provide the latest medical research findings and breaking medical news commentary.

{ 0 comments… add one now }